On the surface of things, Fritz Lang’s seminal Metropolis is one of the greatest silent films. It is an incontrovertible hallmark of the science-fiction genre, having paved the way for ambitious, futuristic films such as Blade Runner, Gattaca and even Star Wars. The epic sets, atmospheric aesthetic and notable set pieces; characterised by a grandiosity not yet seen in cinema, ushered in new and exciting cinematic conventions that exist to this day.

Buried beneath the marvellous varnish of Metropolis is a political film that demands our attention. The times in which the film was made – 1920’s Germany – provided a great deal of inspiration for Lang to ground Metropolis in a basically political context. Even though Metropolis takes place in 2026, it is clear that Lang seeks to comment on the contemporary state of German working and economic life. Or at least on the trajectory of German society.

Germany had just suffered defeat in WW1. It had no choice but to sign the treaty of Versailles – its soldiers were dying, and the people of Germany starving. Its allies were vanquished into non-existence. Consequently, Germany agreed to pay significant war reparations to Britain and France, and it ceded 13% of its land.

Even without the humiliating terms of the treaty of Versailles, Germany was struggling economically. Unemployment rates were staggeringly high, and lines to acquire even the most basic of goods were long. Manufacturing and industrial jobs made up a significant portion of the employment market, but the wages were lacklustre compared to that of pre-WW1 times. Germany’s rich were mostly left unaffected, and class structures began to intensify. Thus, Lang’s Metropolis can be understood as a futuristic take on the imbalance of class and the malice of unfettered capitalism.

The film begins with a group of workers walking mechanically into one of the many factories that lie beneath the surface of the city. Their work is what created, and sustains, the apparently wonderful city of Metropolis. Yet they receive none of the fruits of their labour. The workers are confined to underground factories and tunnels, bereft of the colour and life that seems to define the innovative Metropolis.

The workers are zombified – their labour is exploited beyond measure by the rich industrialists, and they are dormant to the possibilities of working life. They are literally forced to work underground, symbolic of their class position. Lang’s organisation of the workers in a large cluster attends to their untapped potential: a Marxist, active, collectivised proletariat could “break free” of their chains.

This highly-stylised image of an oppressed, asleep working class stays with us. It is a significant point of reference; as we gradually observe the workers seeking to emancipate themselves. The opening of the film is consistent with Lang’s views of the state of 1920’s Germany.

In Joh Frederson, Lang sees all that which is wrong and imbalanced in society. Frederson represents the wealthy, rapacious capitalists of the times. He lives and works in the upper echelons of impressive skyscrapers, far away from the everyday struggles of the workers. Frederson and his kind reap the benefits of the underground labour, without need to set foot in the concrete-laden factories. Lang presents Frederson as a contemptible magnate that values capital over the welfare of his workers.

The first thirty minutes or so of the film aims to set out the disturbing, but stable, class structures. The images of uninhibited wealth, juxtaposed with the despair of poverty, denies that there is anything natural about such social and economic life. Rather, we are compelled to think that there is something deeply unnatural about the status of the ruling class. They own and control the city, even though it is the workers who create and toil to produce the city of Metropolis. Lang urges us to ask: why do the workers live without while the ruling class lives with so much? And a further, more specifically Marxist question: wouldn’t it be better if the workers owned their workplaces?

We get the impression that Frederson’s son, Freder, has been spoiled with luxury and tranquillity. We first see him in the Eternal Gardens, dressed handsomely in an expensive suit. It seems to us he is oblivious to the plight of the proletariat, on account of being sheltered by his father’s hyper-affluence. Perhaps it was inconceivable to Freder that the reality of life for some was far bleaker than his own.

When Maria brings a group of ‘underground’ children to the Eternal Gardens, Freder is enamoured with Maria. Apolitically but romantically drawn to her, there are numerous shots of Freder watching her from afar – he even follows her to the depths of the underground. Maria’s somewhat clandestine infiltration of high society sets off a chain of events that changes the structure of Metropolis.

Upon his physical entrance into the ‘underground’, Freder is horrified to find the proletariat in such a neglected state. Innocent of wrongdoing, but awash in dirt and grime; Freder is immediately sympathetic to the workers. Those feelings are compounded when a machine unexpectedly explodes, killing and maiming many. Freder rushes back to his father’s tower to tell him of the tragedy, but Joh is unreceptive, waving away his son’s concerns. He dismisses the plight of the workers by declaring that “[the underground is] where they belong.”

This is a pivotal scene in the film, representing an unholy clash of the classes. It becomes clear that members of the disparate classes were never meant to meet and interact; for it would inevitably disturb the rigid organisation of class structures. Anew, Lang communicates the unnaturalness of class evident in Metropolis. If it were natural and inevitable, Freder would be unmoved by the sight of a lower class. But he isn’t. Freder is appalled at the working conditions and the converse apathy of his father. He undergoes an awakening, resulting in his siding with the besieged proletariat. The workers, to Freder, are “the people whose little children are my brothers, my sisters.” Thus, he elects to blend in with the workers, bearing the same dirt-stained face and ragged clothing.

After the machine accident, the proletariat grow dissatisfied and angry. Their discussions, at first, are fractured and spontaneous. Maria, as a symbol of power and beauty, assumes the responsibility of being their unofficial leader. In a number of scenes, she stands above the workers, preaching quasi-religious passages that give them hope and comfort. Symbolically, she is closer to Mary than Lenin. Maria does not urge the workers towards violent revolution, but rather towards an inner peace. The most famous of her utterings is surely “head and hands need a mediator. The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.”

She stands atop scaffolding, leaving Freder and the workers in awe of her from below. Maria harnesses the power of the proletariat, collectivising them through quasi-religious paraphernalia and preaching. Although this is discrepant from Marxist ideology, it seems to work to attribute power to those in the underground.

The only problem is that Joh and Rotwang stumble upon one of the meetings of the workers. It is obvious to them that Maria is the force holding the proletariat together, and they return to the towers of Metropolis to plan her downfall. Joh concocts a plan for Rotwang to capture Maria in order to create an evil, violent duplicate of her. Their aim is to fragment the workers and impel them towards destruction, so the ruling class will have a case to forcefully suppress them.

Maria represents the hopes and dreams of the workers – an embodiment of their strong fraternal connections. For the capitalists that wish to quash the humanity of the workers, Maria is something very dangerous, for in hope there is power to act.

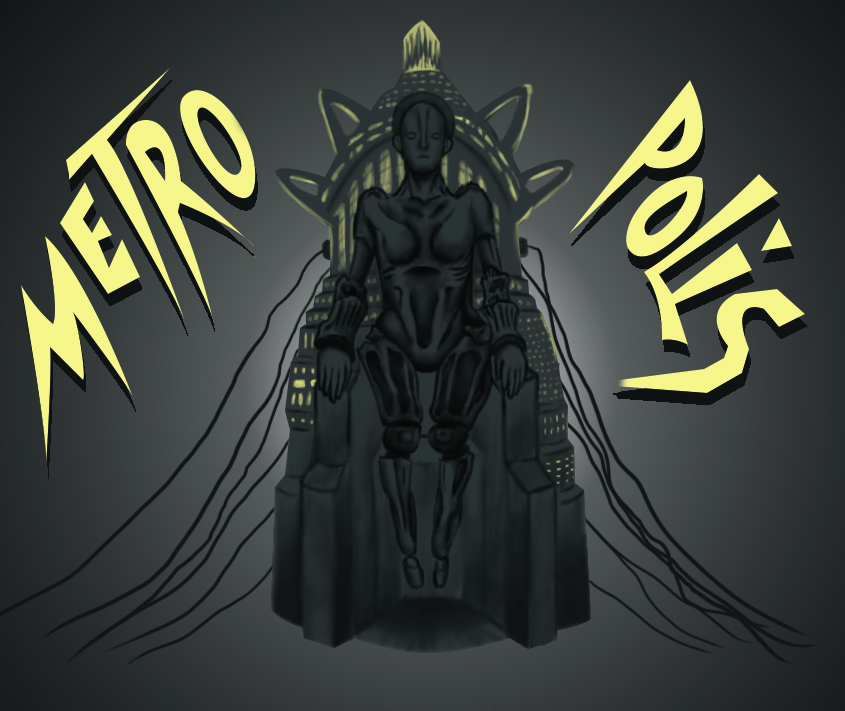

It is telling that Joh and Rotwang use technology as a means to facilitate her fall into disrepute. Lang is certainly conscious of the ways in which the ruling class exploit powerful apparatuses to maintain power: the printing press, destructive weapons and corrupt police officers. The robot incarnation of Maria is a fantastical, futuristic display of what the wealthy can acquire and deploy against those they wish to crush.

In a similar sense, the robot represents a dangerous, almost foolproof future in which the wealthy can discredit the working classes. In the past, the ruling class had used plants at demonstrations, the printing press to disseminate lies and unlawful arrests to portray dissidents as scheming, violent and ‘enemies of the state’. The robot is certainly tethered to this past history, but it is also a futurist warning of the power that capitalists will have in a century’s time. Although robots are not in regular use, the development of technology, particularly the internet, bears out Lang’s worries.

Once developed, Rotwang unleashes the robot on the proletariat. Subject to the whims of an unrecognisably violent, belligerent Maria, the workers rise from the underground to carry out terror against the privileged in Metropolis. The workers rabidly destroy the machines in the city, including the heart machine. This causes the underground to flood, while the children of the workers have been left to fend for themselves. Their lives are only saved by Freder and the real Maria, who rush to sweep up the mess of frenzied workers.

This whole sequence seems to be a thinly-veiled warning against granting one inspiring individual the power to dictate and organise the working class. Although it is not Maria who leads the proletariat on a path of destruction, Lang communicates to us that too much can go wrong with only one symbolic leader. Particularly, Lang acknowledges the ease with which the ruling class can manipulate and discredit the entirety of the working class struggle if there exists one, unquestioned saviour – an apparent rejection of Leninism.

Simultaneously, Lang presents the proletariat as an enormously powerful entity, capable of reshaping and determining the future of an urban city. Even though they initially seek to destroy the city’s infrastructure, the surge capacity of the workers is undeniable. They dismantle, discard and destroy large parts of the city. As an active, united group, the workers have the autonomy and authority to improve or ravage the spaces and conditions in which they live.

Even though Lang advocates against vesting power in one authoritarian leader, he doesn’t make much of a case for the self-determination of the proletariat. They are regularly shown to be mindlessly submissive, lacking the mental faculties to self-govern. The carnage they exact on the city is fuelled by anger that blinkers their common sense – as they flood the places in which their children sleep, play and live. Only after they destroy the heart machine do they realise what they have done. In response, the workers, in a frenzy of revenge, burn the robot Maria at the stake.

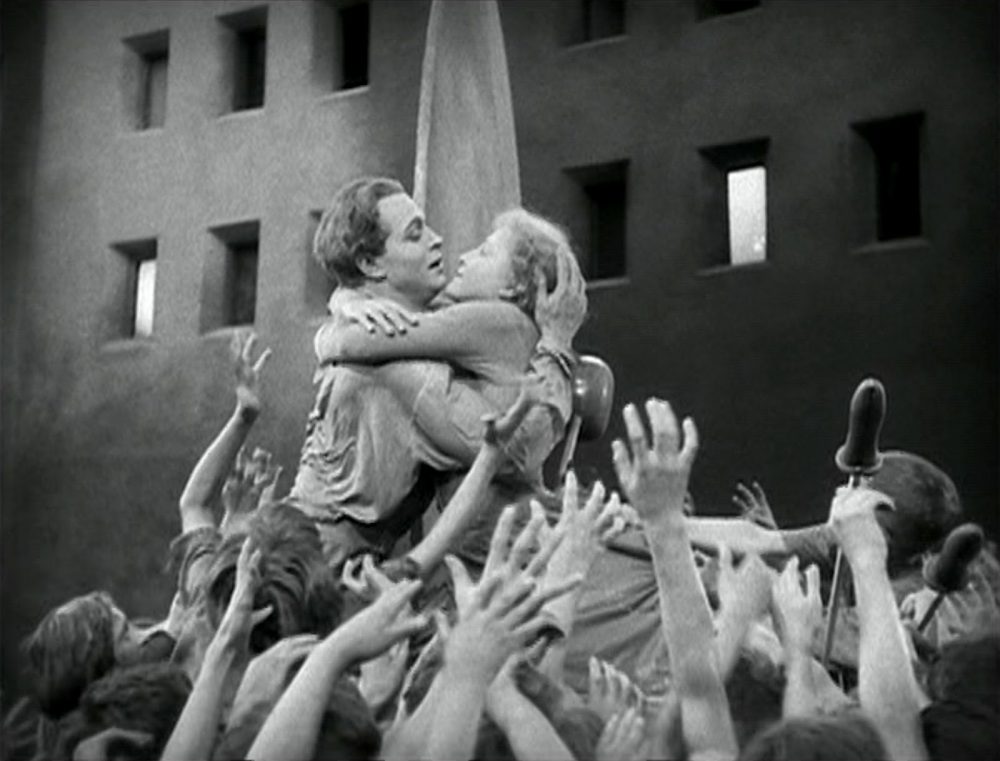

Pure luck saved the workers from murdering the real, benevolent Maria. As she emerges with Freder and the children, the workers exhale with cathartic relief. At best, the proletariat are temperamental; and at worst, agents of self-destructive violence.

Metropolis concludes with an agreement between Joh and the industrialists, and the workers resolve to respect each other and work cooperatively. This is manifested in one of the final images of the film – with Joh, Maria and Freder standing out the front of the city centre with their arms entangled. We are encouraged to view the conclusion with a newfound sense of hope, of productive solidarity. The head and the hands have finally been co-joined by the heart.

What is probably more regularly felt is betrayal. The shift towards social-democracy is indeed jarring and baseless within the film’s context. There is no point at which we see the potential for the working and ruling classes to be reconciled. Rather, they are shown as competing and antithetical. Lang’s compromised ending rings with naïve sentimentality, acknowledged even by himself. In years following the film, Lang labelled the film’s final message “absurd”, and other parts of the film “too simplistic” in evoking the “evils of mechanisation.”

Ultimately, Metropolis is a notable and brilliant film that speaks to the anxieties and ambitions of an under-valued, oppressed proletariat. Even though it often fails to present a coherent political message, the power of its insights into the social and economic structures of capitalism is indubitable. Beyond that, it is a genuinely entertaining and engrossing film that has retained relevance for almost a century.