Last year, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) presented a fantastic retrospective on the American film director Martin Scorsese. As an avid fan of cinema and an even greater fan of Scorsese’s films, I voraciously anticipated seeing his 1976 magnum opus, Taxi Driver, on the silver screen.

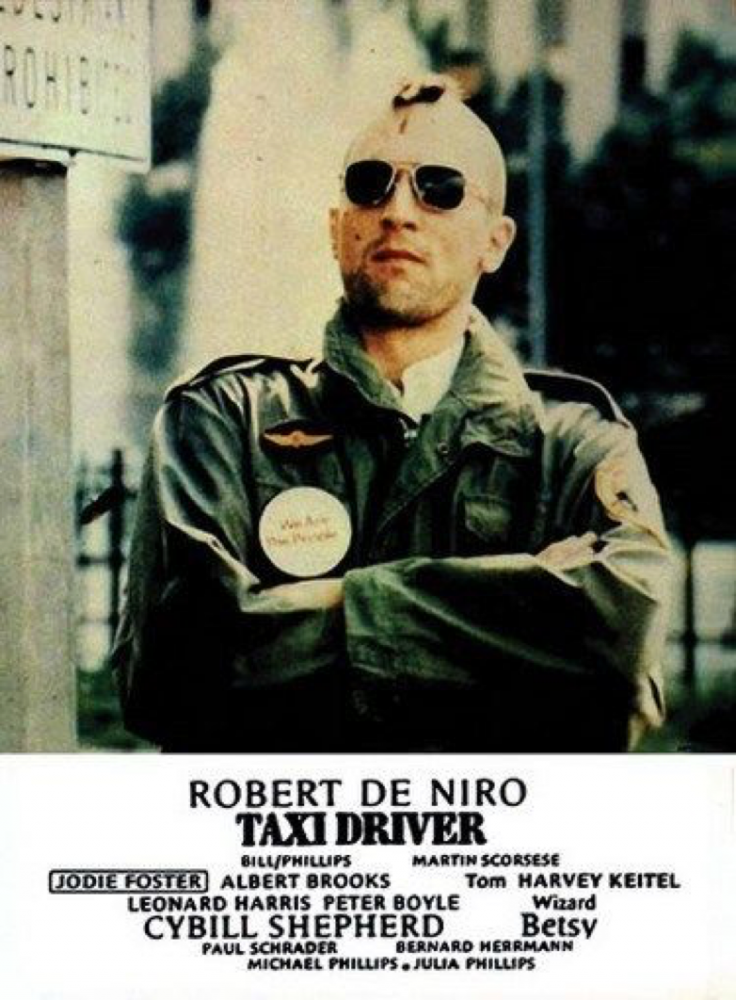

Taxi Driver is a film that immediately places the viewer firmly within the venal streets of ‘70s New York. It throws us into the political and social context of that era as we come to know the anti-hero of the film, Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), a Vietnam war veteran. Other than a brief allusion, we never encounter Bickle’s experience of the war directly. Rather, Scorsese makes us cognisant of the impact of the war through Travis’s behaviour; his sleeplessness, his Army jacket, his snap into a rigid fighting stance when confronted. While the presence of the war surreptitiously lingers in the background of the film, it never really manifests itself as a central thematic concern. Instead, the war paves the way for Travis’s personal ills, giving the viewer greater understanding of the erratic psychological processes embedded within him.

It is no secret that Travis is a character who is profoundly troubled. Scorsese always confronts us with this fact, providing shots of Travis staring contemptuously at African Americans, wandering about with an armoury of weapons, and of course, that famous scene when Travis looks into a mirror and asks: ‘are you talkin’ to me?’

The screening of Taxi Driver at ACMI was powerful, even more so when experienced on the sizeable screen. It was to my utter disappointment, however, that some patrons behind me summed up their viewing experience by a simple denouncement: “he’s a psycho.”

I’ve heard this assessment of the film before, and I have always launched into a robust defence of the complexity of Travis and Taxi Driver. To merely denounce Travis as a psychopath is to deny Scorsese his filmmaking dexterity, while also undermining the genuine human implications of the film.

Indeed, Taxi Driver is a film that perfectly positions us to observe and apprehend Travis’s psychological processes. We are in his mindset for all but two scenes during the entirety of the film. Travis’s ever-persistent voiceover gives the viewer access to his dangerous and unstable view of the decadence of ‘70s America; to his insatiable desire to get rid of the ‘scum’ and ‘filth’. Travis operates as a kind of noir-ish figure – always alone, navigating the streets in his grimy yellow taxi. This feeling of isolation within the urban setting of New York is a pronounced feature of the film, central to understanding the motivations and actions of such a volatile character.

In many ways, Travis is a repulsive character. He is racist, hate-filled, creepy and excessively prone to violence and volatility. However, Scorsese does not unequivocally condemn Travis, but rather illustrates to the viewer how this character is the way he is. We can understand Travis as existing within a real-world framework, and therefore relate his ills – and the ills of ‘70s New York – to our own society.

If we disregard Travis as a one-dimensional psychopath, we deny his humanness. To do so is consistent with the lamentable ways in which ‘the other’ is often fallaciously labelled and compartmentalised in contemporary society.

Indeed, there are quite a number of individuals and groups that are perceived as ‘the other’ in the West; those who are racialised (i.e. not white), those who depart from heteronormative definitions of sexuality; those with disabilities; those who are homeless; those who have committed criminal infractions.

The designation of simplistic labels to those who are broadly considered ‘the other’ is damaging; calling the homeless ‘lazy’, telling women who have experienced domestic violence ‘to get up and leave’ and condemning those who have criminal pasts as ‘psychopaths’ are expedient ways for us to avoid deeper analyses of prevalent social ills. It places blame on the individual, rather than the unequal structure of society itself.

Perhaps the worst thing that this kind of thinking does is that it perpetuates a culture of misunderstanding. Without acknowledging the plights of individuals, we will never begin to reduce suffering and negative discriminations.

Only when we fully comprehend the complexity and multifaceted nature of human existence will we be able to diagnose and resolve problems in modern society. For Travis, perhaps with better veteran counselling and engagement services, and greater reception to his loneliness and bleak outlook on life, Taxi Driver would not have ended in the misanthropic, macabre way that it did.