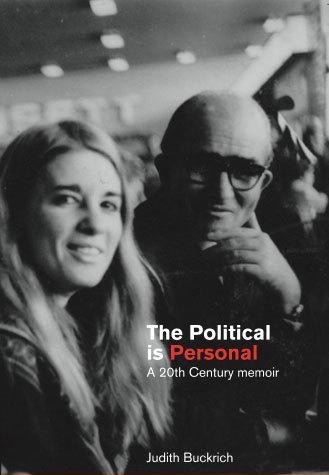

The second wave of feminism, the civil rights movement, the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972. These are socio-political triumphs that seem increasingly distant to us, lost in a labyrinth of penalty cuts, Donald Trump and political disillusionment. It is for this reason that Judith Buckrich’s life and memoir, ‘The Political is Personal’ resonates so powerfully with our generation.

The Political is Personal is a memoir of a life lived daringly, at the intersection of turbulent but thrilling periods of history. Judith Buckrich contextualises her private experience within the framework of events that forged a resurgent, post-World War society and shaped her own journey as a writer, historian and political activist. Vulnerable, wise and witty, Buckrich’s narrative is a challenge to complacency and cynicism, a reflection of the author’s own extraordinary personality.

So it is with a sense of trepidation that I walk through the streets of Prahran, lined with sleek boutiques and snug cafes to interview the author herself. I worry that she will be impossibly poised and confident, a formidable presence.

Instead, I find a person whose laugh is great and generous; someone with warmth, graciousness and humour. Qualities which reverberate through her relentlessly honest writing. In simple, eloquent words Buckrich crafts a fascinating image of a historical era in which baby-boomers believed they could change the world. “An extraordinarily inspiring time, a good time to be alive,” she says fondly, lingering on memories of being a law student at Monash University in the 1960s, at the hub of social and political change.

The Political is Personal reads with the same striking ease, openness and buoyancy that the writer displays in person. I ask her how she gained such authenticity of voice, how she had the courage to expose her private life. Her answer is immediate, direct. “I just am like that,” she shrugs. “I could not have done it any other way.”

It is this fearlessness, this embrace of one’s humanity, that allows Buckrich to speak and write with such passion and intensity about her life. Tumultuous and full of lucky ‘chances’, she admits, one of sheer determination and tackled with an unquenchable zest.

Her lifelong love of literature, she says, was sparked by “voracious reading”. “To be able to read and read and read…that was my world,” she tells me. When I question her about how her interest in history began, she laughs at the memory of how immeasurably boring history lessons were – “Gee, they taught it badly!” – and emphasises how important it is to have “interesting”, “passionate” people teach it. “That’s the thing,” she muses, “if you’re going to be involved in history, you have to understand the ideas that are making a certain time.”

For her, it was the experience of reading Dostoyevsky and other revolutionary Russian authors that informed her understanding of these political notions; writers also well-loved and read by her father, Antal Bukrics, who was a communist.

Both in The Political is Personal and in our interview Buckrich affectionately recalls her father’s influence, mentioning their social, political and metaphysical conversations while “looking at the stars”.

“Growing up with someone who is conscious about what’s going on in the world…is a pretty important thing,” she ponders, relating slivers of her father’s intriguing history as a member of the communist party in the United States and a storyteller himself, who wrote poems that he destroyed and which she tried to recover.

It was at Monash University, however, that the political world really infiltrated Buckrich’s personal life and consciousness. She describes the atmosphere at Monash in 1969, and what it was like to be a university student leaning forward, her eyes lighting up and face animated. “It was,” she says with evocative joy in her voice, “like someone put wings on your back… Monash was the absolute centre of student movement, in Australia, not just in Melbourne.”

Mentally toying with a whole spectrum of memories, Buckrich grasps at dynamic word-pictures, “vibrant, marvellous, fabulous”, conveying that vastly complex and novel experience of new music, theatre, literature, and ways of thinking, speaking and acting. “The Labor Club newsletter came out every single day,” she laughs, “and there was actually a serious article in The Age that said a revolution was going to happen in Melbourne, starting at Monash!”

In a few moments of happy, soaring nostalgia, she paints an exuberant picture for me of “long-haired” boys, dishevelled students arguing at cafes about politics instead of attending lectures, and of watching the moon landing with her boyfriend, “madly in love”, while sitting in the lounge of the Student Union.

“I’ve never forgotten what that was like. We were watching the landing on the moon, and this was a whole new world. It was all somehow to do with us, and to do with our future.” Her voice, contemplative, almost dreamy, immerses me in all the emotion surrounding infinite possibility.

Yet this euphoric stage of her life was far from trouble-free. With characteristic frankness, Buckrich talks about her frustration with largely male-dominated and male-run political movements at Monash. “The thing that spurred me on,” she says emphatically, “was that here we were, supposed to be in this kind of revolutionary state, and it was all the men who were running everything!”

She also discusses the difficulty of reconciling her feminist ideals with the social norms of the time, especially when charting a different, unprecedented course in life. “[It was] the struggle to match the kind of social change that was happening into my own life,” she explains. “I did not espouse the social changes of not getting married, I was very free and had many lovers. But as a first generation of young women doing that…it was full of danger.”

In spite of these obstacles, Buckrich was and is irrepressible, fashioning a path for herself completely unique, entirely her own. In considering the evolution of her career as an author, she is very much a believer in the concept of flexibility and flux in one’s life.

“Who knows how these things happen? Opportunities came along, and I took them,” she tells me simply. “It’s a strange thing, life; something stirs in you, and you follow that.”

It was only in 1991, while she was still working as a teacher, that one of these “lucky chances” materialised, in the form of a friend’s casual comment that she should write a book about St. Kilda Road. In 1996, A History of St. Kilda Road was finally published, leading to a career during spanning thirty-five years in which she has published thirteen books.

Her advice for aspiring authors, therefore, is unsurprising: to be open to every opportunity to write. Her own experience is illuminating, as she gives examples of different social, political and cultural contexts that have opened windows of potential and moulded her identity and authorship, such as moving temporarily to the U.S. in 1971 where she “really became a feminist” and drew inspiration from the Women’s Liberation Movement and activists like Angela Davis.

Thus ‘The Political is Personal’ is significant, a testament to the past, present, and future, to the power of possibility. An idea that started as a tribute to the legacy of Buckrich’s father and which evolved into a story about her parents, herself, and the historical and political events that framed and enriched their private lives.

In view of the present and the future, I ask Buckrich for her perspective on our generation and what we can do to make the political personal in our lives; to engage with a progressively disengaged political system. As I list refugee rights among the social and political challenges of this age, I wonder at the success of young people back then: their rallies, political progress, their hopefulness – all of which we seem to be denied.

Buckrich’s response is refreshingly down-to-earth, and quietly articulate. “Keep explaining to people that these things matter,” she says. “We can’t close ourselves off in a little cocoon.” Ultimately, she brings the historian’s perspective, a touch of needed wisdom and balance in the midst of our culture of media frenzy, and a visionary’s optimism, the greatest gift to our disenchanted generation.

“I suppose the great gift from my father is that of hopefulness, that life is a struggle, you can’t give in, you have to keep on going, not giving way to cynicism, remaining hopeful for the future. As a historian, you do see how things have always gone. There have been periods of such darkness in the world. More than ever, we have to be hopeful.”

Judith Buckrich’s book, ‘The Political is Personal: A 20th Century Memoir’ is published by Lauranton Books and available from Readings Carlton, Readings St. Kilda

(mail order: www.readings.com.au/books), Collected Works (Swanston Street Melbourne), the Prahran Mechanics Institute and The Avenue Bookstore (Glenhuntly Road, Elsternwick).