Student publications like this are often replete with reflective pieces about life-changing semesters abroad. Often students describe finding themselves through the challenges presented by life in a new cultural context. What I found was politics—real politics. The politics of the street.

On exchange in an obscure university town in southwest Germany, I took a four-hour train ride every weekend for over a month, to join the gilets jaunes in France as they attempted to overthrow their government.

For several months now, thousands of ordinary people across France have been revolting against President Emmanuel Macron, the poster boy for neoliberal reform. Elected in 2017, Macron earned the title “president of the rich” through a series of policies aimed at bringing more of society’s wealth into the hands of the elite. He attacked the working conditions of France’s rail workers in 2018, and in the same year tried to restrict young people’s access to higher education. A former banker, and minister for the economy in a previous government, Macron has spent his life getting rich at the expense of others. Yet he claimed that it’s ordinary people like the gilets jaunes who “think that it’s possible to obtain something without proper effort”.

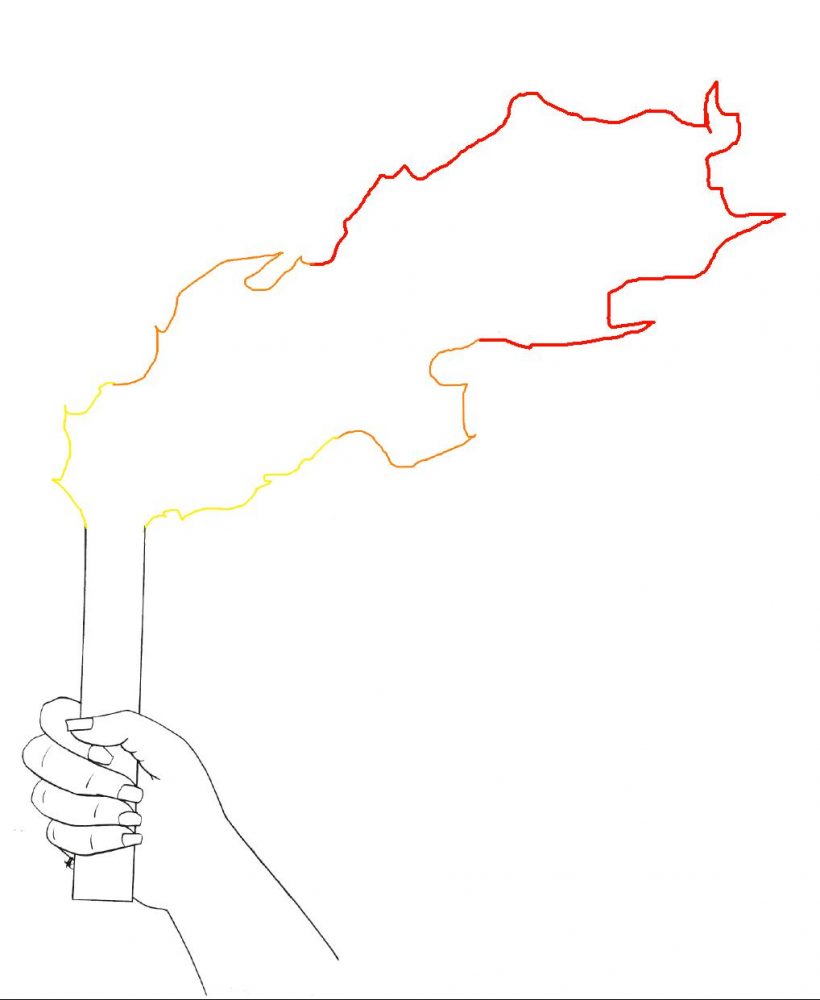

The explosion of this new movement, the gilets jaunes (‘yellow vests’ in English, named after the fluorescent vests that the movement’s participants have proudly donned), was sparked in November 2018 by a fuel tax hike, implemented alongside massive tax cuts for the top layers of society; including an abolition of the inheritance tax for the super rich. Three hundred thousand protestors marched that first weekend last November, blockading roads and occupying toll booths, for the first in what would become a series of weekly Saturday demonstrations.

These demonstrations—’actes’, as the yellow vests call them, like acts in a play—are organised primarily via social media. Participants come from all over France to gather in local city centres. There are weekly yellow vest demonstrations in the major cities like Paris and Lyon, but significantly, some of the proportionally largest demonstrations have been in smaller cities or towns, with populations of only a few thousand, such as Commercy and Bourges.

The language of the ‘acte’ seems to reflect the self-conception of the movement as an ongoing performance, as though each week’s demonstration was a further part in a very long play, edging towards a finale, whatever and whenever that may be.

In December, when I first arrived in Paris for the fifth acte, nobody could say if the yellow vests were going to continue much longer. After five straight weeks of weekly national demonstrations, the politicians and the media were eagerly telling the world that the movement was no more. The number of protesters had declined since the first weeks, and Christmas was looming.

Two of my friends had also arrived that weekend and wanted to take part in the protests. We joined a few hundred yellow vests in the less central Montmartre district—only announced as the rally point at the last minute, to confuse the cops—marching south into the city, chanting for Macron’s resignation. Even in small numbers, the energy of the demonstrators was huge. A few hundred managed to feel like a few thousand.

We had almost made it to the Louvre, a centrepiece of Parisian high culture, when someone looked down a side street. They saw another stream of yellow, reflective vests, marching in a different direction, from some other meeting point we hadn’t heard about. There can be several gatherings of yellow vests in the same city, organised through various Facebook events.

Someone shouted out, others saw the same thing, those of us further back kept pressing forward, excited to see what was going on. The other group had noticed us and was starting to change direction: they were coming to join us! The atmosphere changed immediately, from optimistic defiance to utter joy. We knew in that instant how wrong the politicians and the media had been. This would not be the last of the yellow vests. Everyone erupted into chants of ‘Tous ensemble’—all together!

The protest became a carnival. A young man blasted techno from a speaker on his back, yellow vests dancing around him. As we filled the wide Avenue de l’Opéra, lined with boutiques and expensive restaurants, it felt as though our chants could reach the whole world. We were forcing ourselves into a part of society we weren’t meant to reach, disrupting it.

The police wanted to keep us away from the ultra-rich centre of Paris, especially the Champs-Elysées, arguably the world’s most famous avenue and a focal point for previous protests. Sometimes protesters would argue over which route to take, with some deciding to march left, others right, splitting the group apart. Every time, we would find ourselves again. If the police succeeded in blocking our path, we would march back north before trying a different route.

We would march for eight hours. By the time the sun had set, we had made it to the Arc de Triomphe. It was a symbolic victory over the state which had tried so hard to deny us access to these privileged areas of the city—just as it tries to keep the bottom of society from interfering with the top.

It was only then that my friends and I noticed how tired we were. We had been running from clouds of tear gas. Grenades had exploded near our feet. Heavily armed police had charged at us and fired their notorious “flashball” projectiles in our direction, threatening to do to us, or any of the others, what they have done in past weeks to countless yellow vests who are now missing eyes or limbs. Yet the carnival continued. ‘On est pas fatigué’—We are not tired!

The extreme violence of the French police was captured in a number of viral videos on social media, yet it didn’t dissuade the protestors from coming out—it only fuelled the movement’s anger. After the fourth acte, President Macron was forced to respond with something other than brutality, giving up on the fuel tax that had ignited so much fury. But the fuel tax had only caused a larger reservoir of discontent to spill out, and the yellow vests proved they were here to stay by returning in January, against all the hopes of detractors in politics and the media.

I spoke to a variety of protestors in Paris: a now-unemployed manager of an ice cream parlour; an IT student from Bordeaux, who ran from police with me under the shadow of the Eiffel Tower; and many others. They all agreed that the real issue is the increasingly poor quality of life for ordinary people in France. Demands of the yellow vests include increases to the unliveable minimum wage, as well as broad improvements to social welfare for pensioners and the unemployed.

Deeper questions, about democracy itself, have been taken up by the movement. I’ve watched thousands of booing yellow vests surge past as a waving figure stands atop a news kiosk, wearing the face of Macron, topped with a golden crown, fitting for the monarch he’s seen as, and a not-so-subtle threat in the home of the guillotine. It’s clear to the movement that the people in power are ruling in the interests of a privileged elite. Everybody knew that the concessions from Macron were a pittance at best, and nobody believed him when he claimed he cares about their suffering. He only took notice of ordinary people when they stood up for themselves.

The atmosphere created by the uprising seemed to be spreading far and wide. I saw high schoolers, inspired by the yellow vests to take action themselves, blockading their schools in protest against education reform and marching with their teachers.

I attended huge assemblies of university students, some with thousands of participants, spending hours in open, energetic political debate, on questions of student fees, the racism of the French government, and the relationship between the student movement and the yellow vests.

Yellow vests have also taken part in climate marches, despite the frequent attempts by the French establishment to paint them as anti-environment. Many yellow vests talked with me about how ridiculous it was for the government to claim its fuel tax was an environmental measure, while cutting taxes on the rich, the very people responsible for climate change.

My time in France was an invaluable experience. The yellow vests lack a direction agreed upon by all, and the future of the movement is uncertain, but it has already left its mark on French society, and should send a message to neoliberals around the globe. Thousands of everyday people, normally denied any say in the direction of society, have discovered that they’re able to assert their own kind of power.

Marching in December and January, I saw students, workers, the unemployed, men, and women. Some talked about revolution. Some seemed to think this meant to simply protest forever. Many took up the call for a ‘citizens’ referendum’, intended as a form of direct democracy. Others want to channel the movement into a campaign for the upcoming European elections. Everyone agreed that politicians should have fewer privileges and lower salaries.

The variety of views reflects the organic, spontaneous, and geographically dispersed nature of the movement. There’s no centrally determined leadership or organisation, though there have been reported attempts to form democratic congresses of yellow vests. The yellow vests in Commercy, a small city in north-eastern France, have tried to foster some national coherence by organising an “assembly of assemblies”.

The movement remains small, and in searching for a way forward, the yellow vests may be open to greater influence from right-wing forces, who seek to paint oppressed groups and leftists as the cause of social ills. But the heart of this rebellion is set against the vast inequality of French society, imposed by Macron’s neoliberal regime (as well as those before him).

Anyone looking for a solution to the crisis faced by humanity should look to the gilets jaunes. In Australia as much as France, most politicians are clear on their allegiances to the wealthy, on their contempt for the environment, refugees, and the working class. The yellow vests prove that protest politics is alive and kicking, that ordinary people, robbed of our voices by a world run for the rich, can still take them back.