It is needless to say the political affairs of this country are characterised by complacency, self-enrichment and parochiality. Refugees are treated as subhumans, little is done to alleviate economic inequality, and most enduringly, our Indigenous peoples are afforded no serious concern or attention. The long-overdue constitutional recommendations made by the Indigenous referendum council have barely rated a mention in our national political discourse. Our political leaders have refused to respond meaningfully to the recommendations, let alone demonstrate support for them. On top of that, Australia is the only Commonwealth nation without a treaty with its First Peoples.

This political inertia and indifference is not going unchallenged. Indeed, Indigenous Australians – in academia, in journalism, in theatre, in cinema, even those in politics – are fighting admirably for greater acknowledgement, consultation and respect. This is a collective effort, the success of which hinges on the concurrent and cooperative activities of Indigenous leaders in myriad fields of life, to educate and progress our society from various angles.

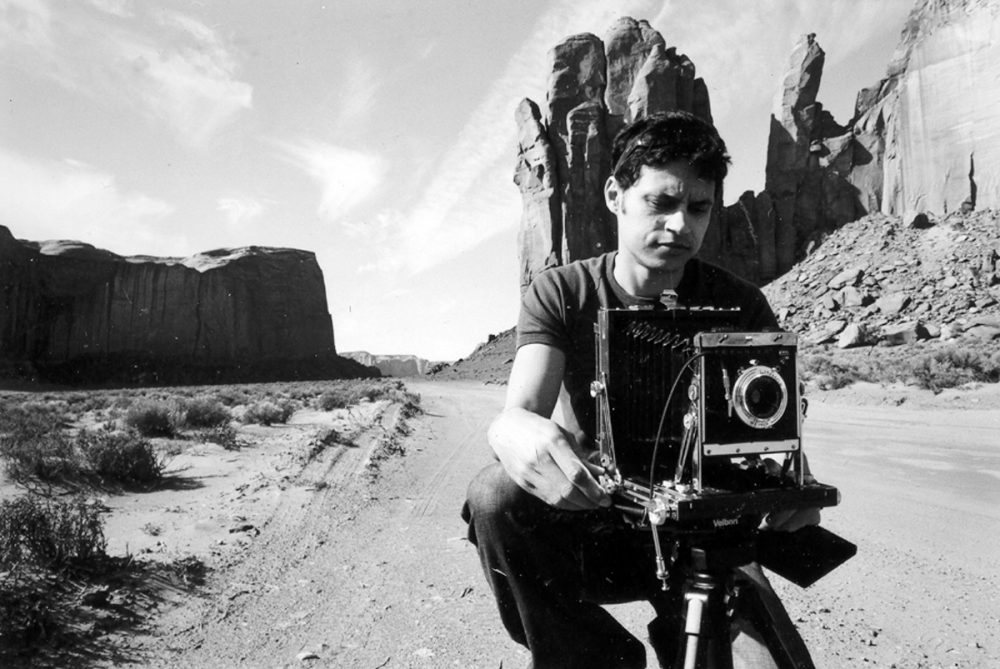

Ivan Sen is one of those leaders, an ardent advocate for the advancement of Indigenous Australia, an excellent role model for its emerging generations. Sen was born to an Indigenous mother, and a European father in rural New South Wales. From an early age, Sen regularly wrestled with questions of identity, of culture, of belonging. He has spoken openly of his familiarity with “being torn between two cultures,” remarking that he was embraced by his Indigenous family, but felt like an outsider amongst them; his white relatives accepted him, but they treated him differently on account of his Aboriginality.

This liminality – having a foot in both camps – has recurringly manifested in Sen’s work to date, most notably in the Detective Jay Swan films, Mystery Road and Goldstone. Sen first engaged with matters of racial identity, though, in his debut feature, Beneath Clouds. Lena, a young girl of Irish and Indigenous heritage, is our main subject of interest. She lives in an isolated Indigenous community with her neglectful mother and step-father. Lena evidently loathes them, and cannot envisage a productive life in the town. “You’re never gonna get out of this shithole,” Lena tells her young, pregnant friend, Ty.

Lena leaves the town to live with her Irish father in Sydney. On her journey, Lena repeatedly encounters a wayward Indigenous teen, Vaughn, whom she finds abrasive and hopeless. He has broken out of prison to visit his dying mother. Beneath Clouds follows the respective but divergent journeys these two lost adolescents take. It would be fair to say Sen primarily focuses on Lena, paying substantial attention to her dislocated place within Indigenous culture. Lena tries to suppress and deny her Indigenous roots, telling Vaughn that she is only of white heritage. In view of her circumstances, Sen does not condemn Lena, but rather attempts to understand her crisis of cultural identity. This is achieved effectively through Sen’s unrelenting probing and interrogation of Lena through image: examining every quiver, grimace, smile and look of hesitation etched on her face.

Undoubtedly, the crux of Lena’s crisis is linked to the Indigenous experience since the colonisation of Australia. Throughout the road journey, Sen weaves in motifs of Indigenous dispossession, neglect and disadvantage to explain and sympathise with the historical plight of Indigenous Australia. Generally, Lena is received warmly by the strangers her and Vaughn meet. Vaughn is not, and it’s clear why. When Vaughn follows Lena into an outback pub, the locals make a point of staring resentfully at him. When Vaughn approaches a car that Lena has waved down, the elderly driver drives off without them. At play here is the intractable mark of centuries of racial oppression, which patently continues to this day.

This key concern of the Indigenous ‘malaise’ is the main subject matter of Sen’s 2011 film, Toomelah. Filmed in a real remote community, with non-professional actors, Toomelah is a disarming portrait of racial disadvantage and its consequent effects. Sen’s realist approach in Toomelah effectively blurs the lines between fiction and documentary, delivering us a challenging but important cinematic experience.

The titular town in which the film is set – Toomelah – was formerly a ‘reserve’, before becoming a ‘mission’. Now it is an Indigenous community, upon which the horrors of the past have been imprinted. Gran is often confined to her dark, dingy room, immobilised by what she has experienced. Daniel is a young boy often left to fend for himself; his mother is sporadically present, and his father is an alcoholic. Like any child, Daniel is prone to bad decision-making, finding himself absent from school and friends with a local gang of drug-peddlers. Daniel is good-natured, a small innocent child exposed to tribulations most could not conceive of. Sen disposes us to unconditional sympathy for Daniel; when he fights another boy, Tupac, we lament, and when he shows interest in a friendly girl, we quietly support him. And when Daniel is urged to return to school, we intensely hope that he does, for education might be his ticket to a better life.

Sen anchors his films in a history steeped in misfortune, mistake and malevolence. Importantly, his films never drift into nihilism, but rather present nuggets of hope for the future of Indigenous Australia. Lena desperately craves for a bright future, and Daniel has the power to find a new, profitable path. Detective Jay Swan will continue exposing corrupt, self-serving white bureaucracies that trample on Indigenous rights and freedoms. Ivan Sen’s appraisals of, and visions for, Indigenous peoples are most indispensable.