The fight against climate change is ramping up. As mines like Adani pose an ever-greater threat to our future, we should look back at another campaign which fought against the corporate destruction of our environment. In the 1970s and 80s, the Australian nuclear industry was challenged by a movement that drew hundreds of thousands into the streets and saw organised workers across the country directly threaten the business of uranium corporations. The industry was held back from the worst possible extremes by the strength of ordinary people, though it ultimately managed to survive. We need to learn the lessons of this movement, its successes and its failures, if we want to make the current fight against our own extinction the last fight of its kind.

Uranium mining in Australia had been an environmental disaster since it began supplying the British nuclear weapons program after WWII. Mines employed migrant workers who were not informed of the hazards of uranium and leaked enormous amounts of dangerous radioactive materials, such as radium, into the water system. Indigenous people were ignored as state-funded prospectors scoured their lands for uranium deposits, and bomb tests poisoned their communities with radioactive fallout.

Above it all loomed the existential threat of nuclear war. For the mining firms and the politicians, the proliferation of the most destructive weapon ever conceived was all the more encouragement. After all, Australia has the largest known uranium ore reserves on the planet; there were profits to be made.

Corporations and governments around the world worked hard to convince people that uranium and the atomic bomb were safe and in the public interest. The United States ran a project to “highlight the peaceful application of nuclear explosive devices and thereby create a climate of world opinion that is more favourable to weapons development and tests,” to quote the chair of the US Atomic Energy Commission. The owner of the Northern Territory’s Ranger mine spent $1 million (over $7 million today) defending its operation to a 1975 government commission investigating the safety of uranium mining. For decades the details of nuclear testing and its consequences were hidden from public view by a veil of military secrecy.

However, those in power couldn’t stop the growth of a mass environmental consciousness, which led to protests against oil drilling in the Great Barrier Reef, as well as union “green bans” during which construction workers refused to work on projects that threatened urban parklands, historic buildings and public housing. Protests held against French nuclear tests in the Pacific Ocean showed an increasing concern for the effects of the nuclear industry. The Whitlam Labor government, elected in the wake of the movement against the Vietnam War, planned to put a hold on uranium mining until global ore prices had risen, but this allowed them to pay lip service to the Aboriginal land rights campaign in the meantime.

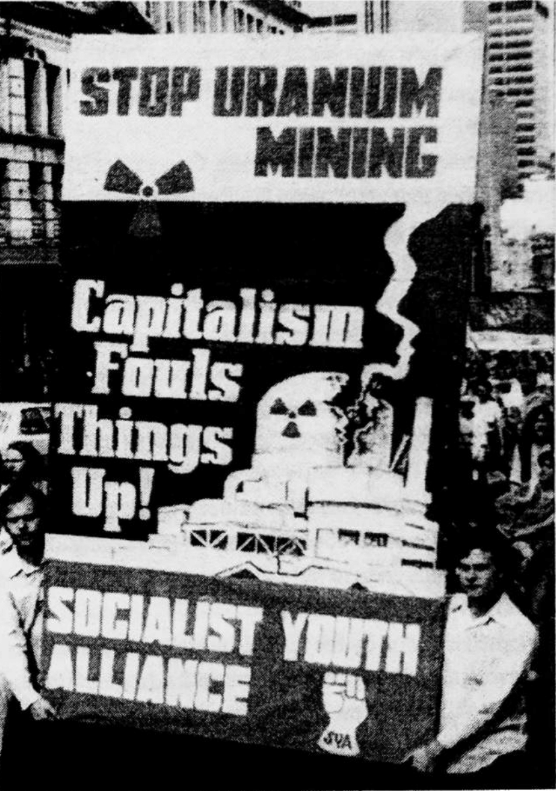

In South Australia, home of the world’s largest uranium ore deposit, 500 people protested on August 6, 1976 – Hiroshima Day – after mining resumed under the freshly elected Coalition government under Malcolm Fraser. When Fraser announced that 10,000 tonnes of uranium exports would be permitted, 4000 people protested in Melbourne. The protests were accompanied by the action of unionised workers. The Australian Railways Union (ARU) shut down the country’s rail network when a railyard worker was sacked for refusing to transport materials en route to a Queensland uranium mine. The worker was reinstated after 24 hours.

In April 1977, 20,000 anti-uranium protestors marched throughout the country. Police attacks on anti-uranium wharf pickets in Sydney and Melbourne led to dockworkers in Victoria refusing outright to work on any ships carrying the material.

From March to September 1977, polls showed that opposition to uranium mining had doubled in places where the movement was most active. Not only were minds being changed about uranium, they were being convinced in the thousands to join the fight against it, and the protest movement grew rapidly. That year, 50,000 people rallied for Hiroshima Day. Then, 70,000 marched in October, including thousands of workers in their unions.

The government fought Aboriginal land rights demands, insisting on the right to deny them where the ‘national interest’ was at stake – that is to say, where they would impact mining operations. Aboriginal leaders were bullied into compliance. In signing an agreement for the Ranger mine, Fraser told the head of the Northern Land Council, which represented communities in the Northern Territory: “Shut up and sit down…you will lose the [NLC]…I will take it off you…you won’t have anything.”

In 1979, several more trade unions implemented work bans related to uranium mining. The Transport Workers Union refused to move mining goods anywhere in the country. Metal workers, railway workers and electrical workers all refused to work on the construction of uranium mines or with any associated equipment. Construction material, shipping, power and communications were all denied to mining companies, cutting profits by two-thirds at the Mary Kathleen mine between 1980 and 1981.

In 1982, the campaign drew out 100,000 demonstrators in April. The same month in 1983 saw 150,000 around the country. It began to take up slogans against war and imperialism. Demands chosen by a 1984 organising conference attended by 52 campaign groups included the rejection of US military bases in Australia and nuclear-free zones in the Indian and Pacific oceans. The largest Australia-wide day of protest in history (prior to the 2003 anti-war demonstrations) took place in 1984, with 300,000 marching, including 150,000 in Sydney and 100,000 in Melbourne.

It became impossible for the industry to operate to the catastrophic extent desired by its proponents in the 1980s. Business was hindered by the activity of ordinary people organised in their own interest, rather than the interests of capitalism. Immense demonstrations showed a growing and vibrant movement, thousands of people who were willing to actively challenge the status quo. Workers among them were convinced to use their industrial power to interfere with uranium production at the source. The experience of this struggle was leading people to connect issues of war, racism, and capitalism.

Yet the nuclear industry never disappeared entirely, and is on the rise again today – the campaign of the 80s was a partial victory at best. In fighting climate change, we need to carry the spirit of the fight against uranium to its logical conclusion: the end of all inhuman devastation taking place in the name of profit. That means understanding where the campaign faltered.

As early as 1977, the Australian Labor Party (ALP) had been won over to an anti-uranium position, calling for a ban on the industry at its national conference, lending hope to many that a Labor government would finally outlaw uranium altogether. The party even endorsed the 1978 Hiroshima Day rally. However, by 1982, Labor’s position had softened to the misleading policy of “no new mines”, with an exception for mines which did not mine uranium exclusively – if a mining firm happened to dig up uranium while also mining copper, tin or gold, the Labor Party wouldn’t complain. Once an ALP government under Bob Hawke had emerged victorious from the following year’s federal election, the party took another step back from its promises and adopted the so-called “three-mine policy”, allowing at most three uranium mines to exist at any one time, more than enough to satisfy the industry while Labor sabotaged the anti-uranium campaign.

A key contributor to this sabotage was Hawke’s destruction of the workers movement. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, half of all workers were members of a union in 1976 (in 2016 the figure was 14%). Strikes were legal and common and because workers fought for a greater share of the pie; wealth inequality was much less severe than today. But union leaders, generally bureaucrats and lawyers paid to negotiate with employers, are always under pressure to compromise – striking a deal is easier for officials than leading a strike to victory.

In the 70s, this was expressed as a serious division in the union movement, as the union leadership was pressured on one side by the self-directed activity of radical workers, and on the other by the conservative instincts of officialdom. Many instances of industrial action, including the 1977 ban on uranium in Victorian ports, were carried out by workers against the will of higher-ups in the union.

The Prices and Incomes Accord, an agreement signed by the Hawke Labor government and union leaders in the 1980s, ensured that bureaucratic conservatism won out in the end. The unions committed themselves to a no-strike pledge, supposedly in return for a better deal for workers at the level of government – guaranteed wage rises and greater social spending, without the struggle. In reality this was a con, a pledge from the bureaucrats in the unions and the ALP to serve the cause of big business in return for political backing. Using their position of influence over large numbers of people who rightly hated the Liberals, they ushered in the greatest transfer of wealth from the bottom to the top of society in Australian history. Workers were convinced not to fight against privatisations and cuts brought in by Hawke and his successors.

The minority who refused to capitulate found themselves under attack not just from the government and the bosses as usual, but now from other unions too. The militant Builders Laborers Federation, responsible for the environmentally-conscious “green bans” of the early 70s, was notoriously smashed by the combined efforts of Hawke’s government and the right-wing Building Workers Industrial Union.

The anti-uranium movement failed to challenge Labor, allowing the growing campaign to stall as activists waited for the party to enact change, while the party in fact worked to shatter the campaign. Under the three-mine policy, the uranium industry, though restricted, would survive while the opposition withered away, confused and demoralised in the face of half-measures implemented by the “pragmatic” Hawke. The campaign’s most effective weapon, industrial action, was subdued by the very government the union movement helped elect.

Today, ALP politicians argue that workers’ interests lie with coal mines, but it was the ALP that forced workers to become dependent on bureaucrats and ‘job-creating’ corporations. They smashed up our means of fighting on our own terms. Not only did they destroy the historical right to strike, they undermined workers’ confidence in our own collective strength, pitting us against each other and telling us we had to settle for what they would provide from on high.

We are the ones who have the potential to force real and lasting action on climate change, just as a mass movement of street, student and workplace activism posed the greatest challenge to the 1980s nuclear industry. The Labor leaders, who joined the movement when it was electorally useful, ultimately fought to save uranium mining. Now they openly champion the fossil industry, flying in the face of majority opinion.

The anti-uranium campaign shows that it’s possible to build a serious and principled opposition to environmental destruction, that could inspire thousands to join the fight for the future. We can see the start of this already, with tens of thousands marching in school strikes, with mass civil disobedience from groups like Extinction Rebellion. We need more of this, and we need it to go further. The most important lesson to take from the struggle against uranium is the need to fight for a different kind of politics, one in which ordinary people actually take the lead. No more appealing to the mechanical hearts of aspirational bureaucrats. We need to decide our own fate, not just accept the options presented to us by the top of society.

We can’t afford partial victories anymore.

Oscar Sterner is an Arts/Science student, a member of the Monash Socialists, an environmental activist, and a rank-and-file member of the National Union of Workers.