WHAT IS ‘PIVOT’?

A RECENT HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

Whilst the word “pivot” tends to be feared by overly cautious career politicians, shifts in policies have become a recurring theme in modern politics. With greater economic and political volatility, our leaders continue to protect domestic interests through changes to short-term and long-term strategic goals. Although policy pivots have aimed to advance the position of a country in the anarchic international order, all changes have had ramifications on both a domestic and international stage.

Pivot to Cold War Hostilities

The end of the Second World War brought about a supposed lasting peace. In London, the British Royal Family, flanked by PM Churchill, waved to cheering crowds. Parades and celebrations took place throughout the United States, notably the V-J Day kiss in Times Square. Moscow was out in pomp with the longest and largest military parade ever in Red Square. Celebrations were ripe throughout the corridors of power with optimism that peace would endure because of the formation of institutions such as the United Nations.

Nevertheless, these jubilant times, with the USSR allied with the United States and the United Kingdom, were short-lived. A swing to animosity and distrust occurred over Europe’s future and growing military power. Propaganda emerged describing the USSR as the “Red Iceberg” that America would hit whilst Stalin was depicted as a malevolent dictator. With increased nuclear capabilities and both belligerents dividing Europe between East and West, the pivot from momentary peace to proxy conflict was afoot.

Never before on the face of this Earth could two feuding factions threaten the world with complete nuclear Armageddon. Intensified through the formation of collective security institutions such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the Warsaw Pact, warfare seemed more probable. These tensions were further provoked by the US pivoting from its long-term isolationist policies to shape the new global world order through institutions such as the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. In turn, the USSR would continue to challenge the ideological base of this pivot and the American’s intervention in key regions. Such animosity persisted until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Pivot to American Hegemony and Globalisation

The close of the Cold War with the fall of the Soviet Union left one superpower – The United States. As Soviet flags were lowered on 25 December 1991, the stars and stripes remained emblazoned. Whilst Russia would slowly recover, the world stood in awe of America’s military and economic supremacy. Not since the era of Pax Britannica (“British Peace”) ending in 1914 had there been a global hegemonic power. The U.S. had a domineering voice in the UN, guided the terms of world trade through reform of the World Trade Organisation (formerly the GATT), held the most votes in the IMF, and upheld NATO. The US was now the sole steward of the international order.

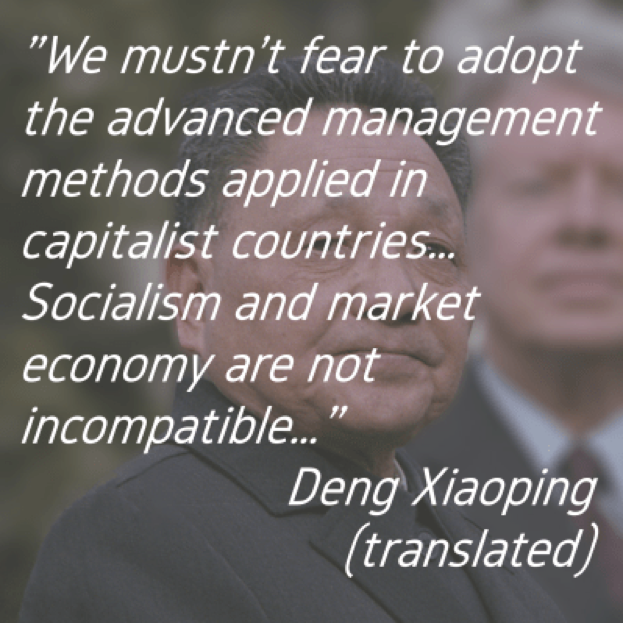

Described as a “unipolar moment” by columnist Charles Krauthammer in 1990, the United States was not only materially superior but ideologically dominant. Socialist movements in many countries collapsed. Notably, China and Russia, the bastions of communism, pivoted towards capitalism and freer markets. Both joined the WTO in 2001 and 2012 respectively. China has signed and implemented 14 free trade agreements while Russia has sought trade agreements with the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and other Eurasian states. The world had now pivoted to capitalism; the United States its driving force.

Neorealist scholars argued that this would be a short-lived pivot. Kenneth Waltz asserted that unipolarity is “the least durable of international configurations.” Yet, it did persist beyond the millennium, weathering events like the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks. The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) finally marketed the end of this era and a pivot to one of greater economic uncertainty. Nevertheless, the pivot to US unipolarity left a major mark on current economic structures which will continue to persist into the foreseeable future.

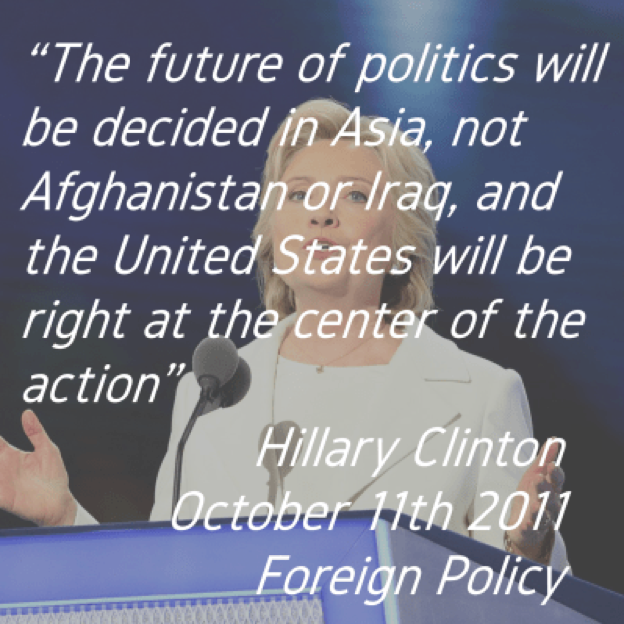

Obama’s Pivot to Asia and the “Asian Century”

Coming to the presidency in the midst of economic turmoil, the newly elected Barack Obama faced the challenge of re-stabilising the American economy after the worst financial crisis since 1929. Contrasted to the events of the Great Depression and the panic of protectionism, Obama instead sought further integration with global markets. Shaping this policy with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Obama sought to pivot the focus of foreign policy from the Middle East to emerging markets in Asia in order to aid the post-GFC economic recovery and reinforce America’s global position.

The GFC was not only detrimental to the country’s strength and stability, but it threatened the international economic order that the US had championed since the Second World War. On the contrary, the Chinese economy demonstrated resilience, not stagnation. In 2009, Chinese GDP grew by 9.7% while US GDP decreased by 2.8%. As of 2016, GDP growth stands at 6.7% and 1.6% respectively. At the current rate, the Chinese economy will overtake the US by 2050.

The recognition by the United States of Asian centrality in the post-GFC economic order not only suggests, but strongly proves, a move away from Western-centric institutions. Chinese supported institutions such as BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) have grown exponentially while the nation is heavily investing in regions such as Africa. Consequently, the ascendancy of the Asia-Pacific, representing 4.5 billion people and over 40% of global GDP, marks a pivot away from US dominance and a path to multipolarity in the next stages of the twenty-first century.

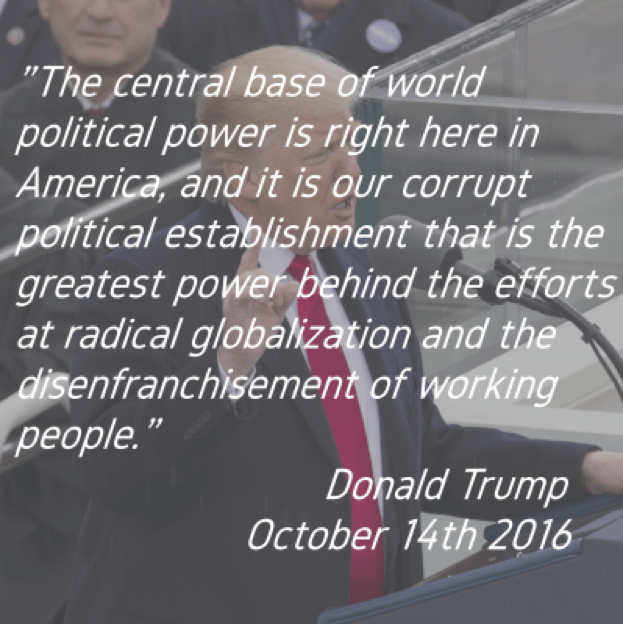

Pivot to Populism?

The Pivot to Asia and Obama’s economic doctrine contrasts the rhetoric of the Trump Administration. Reminiscent of the protectionist policies of the Great Depression, Trump’s “America First” stance is feared to alienate the US from much of the international community. His term marks a rapid shift in the electoral basis of the West. Working classes who have been devastated by policies of free trade, which led to their jobs being shifted to cheaper markets overseas, have awoken and are more actively challenging the political establishment.

However, it is unfair to claim this is only true in the United States. Preceding Trump’s elections, the Brexit referendum also revealed dissatisfaction with rapid globalisation. Specifically, a study by John Curtice of the University of Strathclyde noted that 31% of leave voters did not see any economic benefit from EU membership. Voters also cited dissatisfaction with limited sovereignty and increased immigration. Ultimately, Brexit redefined the anti-globalisation movement with further criticism sprouting throughout Europe.

Although decisively electing President Macron, the French Presidential Election in 2017 also symbolised a pivot from conventional politics. The election was the first in which a major party representative did not proceed to the second-round of voting. Instead, centrist Macron and right-wing Le Pen challenged each other for the keys to the Elysee Palace. While Macron won with 66.1% of the vote, Le Pen’s 33.9% indicated a growing movement to the right. With further discontent regarding the EU and immigration policies in the wake of the November 2015 Paris attacks, Le Pen’s result overshadows the comparatively abysmal 17.8% her father garnered in 2002. Also evident with the robust electoral basis of Forza Italia and the Five Star Movement in Italy, the Freedom Party in Austria and the Alternative for Germany Party (AfD), this result not only represents growing disaffection within society but a sudden pivot to populism unseen since the interwar years.

The future of our world

Pivots in global politics are a norm. The nature of our global order is one of flux, not permanence. The governments of different nation-states will always try to get the edge, at all costs. Regardless, if you are highly averse to such pivots in both the domestic and international arenas, then it is time to realise that the world as we know it will change sooner rather than later. Shifts in policy are becoming more common and we must resign ourselves to such volatility.

This article was produced by Pivot – A MIAS Publication.

Read more like it at pivot.mias.org.au