Who will be Trump’s presidential opponent, and can they overcome his anti-democratic antics?

By James Qumsieh

Donald Trump won’t win. It’s what I tell myself every day. In 2016, I fully expected Hillary Clinton to win, as I think most people did, including Donald Trump. So when she lost, I was in shock because I had assumed for months that she would win, and I was waiting for the results to only confirm my assumption. Since then, we have learned a great deal about how the President actually won, including his campaign’s coordination with Cambridge Analytica and theirs with Facebook. Donald Trump could win again, though – the structures that led to his win are mostly still in place, but one of the few things that could stop him is the strength of his opponent.

The Long and Winding Road

So, who will win the Democratic Primary, and can they beat Trump? The short answer: I don’t know and I’m not sure. The long answer…

Primaries are a long and winding process that ideally lead to a presidential candidate capable of uniting a large-enough coalition of voters to defeat their opponent. Primaries usually take place over six months, but campaigning toward them can last over a year. This is in stark contrast to parliamentary systems like Australia’s, where party leadership is determined in a matter of weeks, and election campaigns last around one to two months. Primaries are a very democratic method of selecting a presidential candidate – unlike most presidential countries, it is a poll of voters, not their representatives in the legislature, who choose their candidates. So, what actually are primaries?

In the United States, primaries are essentially a poll of each state and territory where voters choose who they want to be that party’s presidential candidate. These take place in a certain order, almost random at first glance; in 2020, Iowa is first on February 3 and Washington D.C. last on June 16, with the major parties’ nominating conventions expected around mid-late July. Some states hold open primaries, where any registered voter can participate, and some hold closed primaries, where only registered members of the respective primary’s party can vote. Although primary is a term usually used to refer to the entire six-month-long process (as I have here), it also refers to a specific type of election where voters show up, mark their selection on a ballot, and leave. This process is what most people imagine when they think of voting. Some states and territories, however, hold caucuses. There are two types of caucuses, but we’ll only go into one: mass meetings (also called assembled caucuses). While only seven states and territories hold caucuses, they’re important because Iowa – the first primary state – holds caucuses, specifically mass meetings. We’ll go into the significance of Iowa in a moment, but what you need to know for now is that Iowa is important, and it holds caucuses, therefore caucuses are important.

Move It or Lose It

The Iowa caucuses involve voters showing up and not leaving for a while. Caucuses are held in every Iowan precinct, beginning with voters dividing themselves into certain areas of the caucus site (usually a school gym, classroom, library, etc.) to denote their support. Supporters of Joe Biden, the former Vice President running for the Democratic nomination, for example, will stand in a certain area of this school gym, and other candidates’ supporters in other areas of the gym. Next, voters have 30 minutes to attempt to persuade other caucus-goers of why they should support their candidate, in an attempt to win them over. A count is then taken of each candidate’s supporters, and if a candidate has less than 15% support, then they are declared not viable in that precinct, and their supporters have 30 minutes to choose another candidate. This 15% viability rule means that candidates who do not meet the threshold in the first round will receive zero votes from that precinct. Because caucus-goers get a second vote should their preferred candidate fall short, the 15% cut-off encourages voting for their favourite candidate, regardless of whether they’re an outsider or frontrunner, because they might have a second vote. After these final 30 minutes, votes are secure, and a tally is taken. Results in each precinct are then combined and the total number of delegates won by each candidate is determined. (Delegates are a conversation for another time, but it’s basically the people that will represent Iowa at the nominating convention; delegates won by a certain candidate will have to pledge their support for that candidate at the convention.) If Pete Buttigieg – Mayor of South Bend, Indiana and candidate in the Democratic Primary – earns around 20% of the votes state-wide (or support from caucus-goers), then he will receive around 20% of the delegates state-wide.

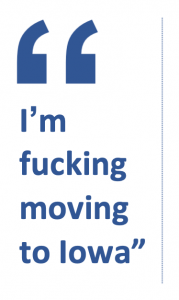

Alluded to earlier, Iowa isn’t only significant because it is the first-in-the-nation primary, but because it helps determine electability. Electability is a term that many pundits love but also many despise, for reasons that will become clear. Candidacies are usually determined by how electable that candidate is – do they appeal to a majority of voters? Can they build a winning coalition of voters? Most importantly, can they defeat Donald Trump? There’s no point in nominating a candidate who can’t defeat Trump, so voters take electability seriously. Electability therefore sways voters towards or away certain candidates because they fear that the candidate might not win, or because they believe that the candidate is, ideologically, too far from ‘middle America’ (Jeremy Corbyn comes to mind). In the primary process, candidates usually choose to prove their electability by winning elections, including primaries and caucuses. If candidates can show potential voters that they have been elected before, then it indicates that previous voters have already vetted them, chosen to trust them and elected them. Joe Biden might not need to prove an electability case anywhere, because he’s already been elected nation-wide. But Andrew Yang (businessman and outsider candidate) might need to prove this, because he’s never held elected office, and therefore has not been vetted by voters. This is the significance of early primary races like Iowa; winning early races like the Iowa caucuses, New Hampshire primaries and Nevada caucuses proves to voters that candidates can win and are electable. Kamala Harris, U.S. Senator from California, was overheard remarking “I’m fucking moving to Iowa” – and candidates have been known to do just this, moving their entire families across states and enrolling their children in Iowan schools so they could focus on the state. It doesn’t work in most circumstances, as Senator Harris could tell you; she dropped out of the race in early December.

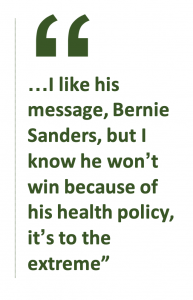

Often, though, voters claim their affection for one candidate, but choose to support another because they believe their favourite is unelectable. An undecided participant in the Los Angeles Times’ focus group, which was held during and after the December debate in the Democratic Primary, remarked that “…I like his message, Bernie Sanders, but I know he won’t win because of his health policy, it’s to the extreme”. Asked who she will vote for instead, Makeba answered, “… Joe Biden, because I know he can win in the swing states”. And Makeba isn’t alone.

This type of voter sentiment is also generally gauged in opinion polls of likely Democratic voters, with 52% of respondents showing confidence in Biden defeating the President. However, head-to-head polls (which ask whether the respondent would vote for Trump or a certain potential Democrat) sometimes contradict this, showing Bernie Sanders, the U.S. Senator from Vermont, and also vying for the Democratic nomination, at around the same lead as Biden against Trump, with both sitting at around 49% vs. Trump’s 44%. Also, when asked about whether respondents would prefer a candidate that can defeat the President or a candidate that agrees with them on major issues, usually around 55% prefer the former, and around 39% prefer the latter. This all indicates a high level of structural support for Joe Biden based on an argument of electability, which can, for the most part, only be broken by another candidate’s electability argument.

Put simply, voters don’t like candidates that can’t win, so they may choose to support a certain candidate because they think that they can win, and, for candidates, the best way of proving that you can win – is by winning. Because of this, the Iowa caucuses act as a propeller for the candidate that exceeds voters’ and the media’s expectations, because voters begin to consider those candidates as legitimate options and could choose to change their support.

This is also how winning in Iowa works – by exceeding expectations. The winner does not necessarily have to be the candidate that receives the most support in the Caucuses, and there will likely be multiple winners. If a candidate receives the most votes in the state, then sure, they’ve won. But if they were expected to receive the most votes, and did not significantly exceed this expectation (by leading with a wide margin, for example), then the media would likely report it as an ‘as expected’ result for that candidate, and instead focus on the candidates who exceeded expectations the most – therefore creating momentum for those that did exceed expectations. For example, Pete Buttigieg could earn the most votes in the Iowa Caucuses, but he may not necessarily be a winner if he was expected to receive the most votes. If he doesn’t significantly exceed expectations by, for example, earning a comfortable lead in the Caucuses, then he may not be declared a winner by the press, although technically being the winner.

The Des Moines Register/CNN/Mediacom Iowa poll, widely considered to be one of the most accurate polls in Iowa, showed in November that Buttigieg was the first preference of 25% of likely Democratic caucus-goers, up from 9% two months earlier, with a combined first- and second-preference result of 39%. This means that if the Iowa Caucuses were held during the same time as the poll, then Buttigieg, according to the poll, would have earned a convincing lead in the state. If the Caucuses were held in September, though, Warren would have had held a decisive lead. Back in June though, Biden would have conclusively pulled it out. In January 2020, and Sanders likely would have closely won. This all means that the race is fluid, and therefore expectations are, too. If the Caucuses were held in September, nobody would have expected Warren to place fourth, but that likelihood is now only growing because they are held in February, and her support appears to be dropping. Because the race is fluid, the Iowa Caucuses, as well as other early primaries, end up being a timing game. The actual results in Iowa end up being a question of who happens to be surging at the time of the Caucuses, and the winner, a question of expectations based on opinion polling.

I don’t even need the popular vote!

So, electability is important, and exceeding expectations is an important part of this, but what if none of the candidates can defeat Trump? There is a very real possibility of Donald Trump being re-elected, and this possibility seems to only grow by the day. His approval ratings, though, might tell you the opposite. Throughout 2017, the President’s approvals hovered at around 38-40%, and around 43% in 2018. In 2019, it has remained largely similar to the previous year, with some polls showing a slight bump to 44%. For comparison, Obama’s approvals were usually slightly higher, although they were barely ever above 50%. Trump’s relatively low approval ratings should, theoretically at least, hurt him. And sure, they might, but they might not end up being important, anyway. In 2016, Trump received just under 63 million votes, and Hillary Clinton under 66 million. And yet, despite receiving almost 3 million more votes than he, Hillary lost. This is because the United States does not elect its president through a popular vote, but instead through a system called the ‘Electoral College’.

In the Electoral College, each state is allocated a certain number of electoral votes, which is a sum of the number of seats that the state holds in the House of Representatives and the Senate. The District of Columbia (DC) also receives three electoral votes, but territories don’t have any. Since there are currently 435 representatives in the House and 100 senators, with DC entitled to an extra three, there are 538 electoral votes; this means that 270 represents a majority. California is entitled to 55 electoral votes, for example, since it has 53 seats in the House and 2 senators (each state has 2 senators). To win a state and all of its electoral votes, a candidate only has to win a plurality of the popular vote in that state – meaning more votes than all other candidates. This is how Trump won the Electoral College without winning the popular vote, something that has only happened four times – while Clinton received almost double the number of votes as Trump in California, and almost two million more in New York, he had a thin lead in most swing states. This is why it’s often said that, although he won by 77 electoral votes (304-227), a sizeable margin, the election was decided on around 77,000 votes in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. This was the President’s winning margin in these three states altogether. If around 39,000 (a little over half of 77,000) of these voters had changed their minds, or if 77,001 more voters had turned out and voted for her in these states, Hillary Clinton would be President.  More importantly, this means that Trump could win again in 2020, even with a reduced minority of the overall vote. Indeed, pundits have predicted that the President could lose the popular vote by more than 5 million votes, yet win re-election. He could retain all of his 2016 victories, except for Michigan and Pennsylvania, and still win with 270 electoral votes to the Democrat’s 268.

More importantly, this means that Trump could win again in 2020, even with a reduced minority of the overall vote. Indeed, pundits have predicted that the President could lose the popular vote by more than 5 million votes, yet win re-election. He could retain all of his 2016 victories, except for Michigan and Pennsylvania, and still win with 270 electoral votes to the Democrat’s 268.

Is it still democratic if I rig it?

The numbers are murky, however, because of the census taking place in 2020. The census determines the number of seats that each state receives in the House of Representatives, and therefore the number of electoral votes. This means that the composition of the House and Electoral College could be decided by whether people respond to the census. Because the number of seats in the House apportioned to each state is decided by the results of the census, then a severe undercount in California, for example, could reduce its number of electoral votes, meaning that Democrats might need to make up this new deficit elsewhere.

The President has already attempted, unsuccessfully, to suppress the response rate to the 2020 Census, which was already at a low 72% ten years earlier. He tried to do this by adding a ‘citizenship question’, which would ask the respondent whether they were a citizen of the United States. Although it may seem innocuous, non-citizens, particularly undocumented immigrants, were fearful that the government would gain access to information about where they live, and share this information with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); among other things, ICE finds and deports illegal non-citizens, although the President’s administration has stated Census information would not be shared outside of that Bureau. The Administration was sued for attempting to add the question, with petitioners probing the legality of adding the question. The Supreme Court agreed that the question could not be added to the Census, in a 5-4 split decision. Voters might still be wary, though, about responding, and could choose not to if they are uninformed or hesitant, which could hurt Democrats in 2020. With that question defeated, many questions remain over whether Trump could still rely on a suppressed vote in the swing states that delivered him victory in 2016.

Suppressing voters’ participation in democracy is an integral operation in Republican politics – whether it’s through constraining the response rate in the Census, gerrymandering, voter suppression (usually small but co-ordinated efforts to discourage or prevent voting), or other structural methods. Conversely and subsequently, encouraging voters’ participation in democracy is an important component in Democratic politics. In 2020, suppression can be relied upon by Republicans to boost their results, and by Democrats to impair theirs.

Gerrymandering is a term that refers to the purposeful manipulation of voting districts, intended to entrench a specific electoral result, usually in a state. States like Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and North Carolina are heavily gerrymandered (guess which party the gerrymandering favours), which means that, even though Democrats received more than 200,000 more votes than Republicans in the 2018 Wisconsin State Assembly election, they only gained 1 seat, and held 36 seats in total, compared to the Republicans’ 63. The same is said for the state’s representatives in the lower house of Congress – almost 200,000 more votes for Democrats, but only 3 out of 8 seats won. Democrats do engage in gerrymandering, but on a smaller scale. They have also legislated for independent commissions to draw up districts, as is done in most countries, including Australia.

In other circumstances, lawmakers choose to engage in more specific voter suppression. This includes voter ID laws, where voters may be required to show photo ID (or non-photo ID in some states), in an ‘attempt’ to avoid double voting, or individuals voting for other people. These laws have been strongly criticised because they disadvantage racial minorities in many ways. Usually, a poll worker will check their voter roll and the voter’s identification, to ensure that all of the information, including name and address match. However, this means that people with middle names that don’t appear on the voter roll, or people with a missing hyphen in their name, for example, would not be allowed to vote – and this very often impacts voters of colour. It also affects people who don’t have one specific address, such as some Native Americans. Native Americans who don’t have an address might find it difficult to obtain identification, so they might be denied the right to vote in states with strict voter ID laws. Other tactics, such as ones that don’t require a law to be passed, may also be used, such as closing Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV) offices in areas with a high minority population, who usually vote for Democrats. This would force citizens of these areas to travel further to obtain identification, which might discourage some.

Because federal elections in the United States are largely controlled and managed by the states, gerrymandering and other forms of voter suppression do take place in the House of Representatives, and obviously also affect each state’s popular vote in the presidential election. This means that a significant level of suppression in a swing-state like Pennsylvania or Wisconsin could tip the election in Trump’s favour, especially through voter ID laws. Democrats have been trying to combat this, though. Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor in deep-red Georgia, began her own organisation to combat voter suppression, Fair Fight Action. She began the operation in 2018 after narrowly losing to her Republican opponent in the gubernatorial race of the same year. Abrams claims that at least 1.4 million people were purged from voter rolls before the election, and that they were disproportionately people of colour. Abrams’ firm specifically attempts to address suppression in Georgia and Texas, especially by registering more voters, and ensuring that votes are accurately counted. Abrams admits that sufficiently-opposing Democratic (and democratic) structures are not in place, and says that ‘We’ve seen 20, 25 years of voter suppression taking shape and 24 months of fighting back. That’s not the ratio we need’. Voter suppression is a large issue, and could affect the results of the presidential election, but there are systems in place that will attempt to combat this in 2020 and protect democratic elections.

End of the Line

So, that’s it. That’s the long answer. I still don’t know who will win the Democratic nomination, but what I do know is that the winner of the Iowa Caucuses (the candidate that most exceeds expectations) will be in prime position to secure the nomination, should they retain their momentum. The winner of the Iowa Caucuses will also be the candidate who best proves their case for electability, and shows caucus-goers that they are ready and able to win the presidency. I don’t know whether the winner of the nomination can beat Trump, but I do know that Democrats should be, and likely are, pulling out all of the stops to prevent the President’s second term. He will use Republicans’ winning strategies, including voter suppression, to attempt to hold onto power, and Democrats will try (and are trying) to prevent him from doing this. The Electoral College, and therefore the results of the next election, could be impacted by the next Census, but Democrats’ best hope of winning will be to create a coalition that can withstand any Electoral College and win over all swing states. Unless the Democratic candidate can overcome the Republicans’ anti-democratic distortions, we will have four more years of President Trump.

Source List

[1] https://www.realclearpolitics.com/epolls/other/president_trump_job_approval-6179.html

[2] https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/how-trump-could-lose-5-million-votes-still-win-2020-n1031601

[3] https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/03/24/2010-census-early-response-rate/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jul/05/2020-census-trump-administration-still-seeking-grounds-for-citizen-question

[5] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/21/trump-adviser-republicans-voter-suppression

[6] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/15/upshot/2020-election-turnout-analysis.html

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/dec/31/voter-purges-republicans-2020-elections-trump

[8] https://www.vox.com/midterm-elections/2018/11/7/18071560/2018-midterm-elections-democrats-gerrymandering (the first paragraph under “David Daley”)

[9] https://elections.wi.gov/sites/default/files/Canvass%20Results%20%282%29.pdf

[10] https://history.house.gov/Institution/Election-Statistics/Election-Statistics/ (2018)

[11] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2018/03/28/how-maryland-democrats-pulled-off-their-aggressive-gerrymander/

[12] https://www.vox.com/2019/9/9/20850936/gerrymandering-michigan-commission-republican-legal-argument

[13] https://www.aclu.org/other/oppose-voter-id-legislation-fact-sheet

[14] https://www.wired.com/story/voter-id-law-algorithm/

[15] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-election-laws/missing-hyphens-will-make-it-hard-for-some-people-to-vote-in-u-s-election-idUSKBN1HI1PX

[16] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/30/us/politics/north-dakota-voter-id.html

[17] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/10/us/alabama-budget-cuts-raise-concern-over-voting-rights.html

[18] https://newrepublic.com/article/152141/2020-election-come-voter-suppression

[19] https://fairfight.com/about-fair-fight/

[20] https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/30/us/politics/georgia-voter-purge.html

[21] https://fairfight.com/why-we-fight/

[22] http://cdn.cnn.com/cnn/2019/images/09/21/desmoinescnnpoll.pdf

[23] https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/6144333-a2190-Meth-07-9-2019.html

[24] https://www.realclearpolitics.com/epolls/other/president_trump_job_approval-6179.html